How I Got Here

In 1948, the year of my birth, Florida’s population was 2.5 million. It still had not reached 3 million when my parents built a home outside of Ft. Lauderdale in 1951. Surrounded by woods with rough-and-tumble friends to play, explore and scrap with, it didn’t take me long to find my first love—a snake! My childhood fascination turned to obsession, which set me apart from the other boys. Through school I endured the nickname “Rep” (for reptile), “Snake Boy,” and worse, but most accepted my fascination with reptiles as normal, if quirky.

Red Ratsnake, Miami phase (Photo: Dick Bartlett)

Snake cages in our barn, early 1960s.

A move to Davie in 1958 changed everything. Life on a farm and new friends who collected snakes put my interest in high gear. By high school, after reading everything in the school’s library on reptiles, and animal collectors, an explorer’s life became my goal. How I’d make it happen was another thing. It didn’t much enter my mind. One way or another, I knew I’d succeed.

Life was a series of escapades: hunting snakes and wild animals, with the scratches, bites, stings, and close calls you might expect. As a high school junior, a job with Blue Ribbon Pet Farm, an animal import company in Dania, Florida, did much to solidify my resolve, and gave me valuable experience. My family tolerated my obsessive hobby at home on the farm but did not encourage it. I remained oblivious to my detractors and set a steady course to a life of adventure.

After joining the South Florida Herpetological Society in 1965, new friends opened doors to what before had only been dreams. Their collections of reptiles were exotic, filled with venomous snakes and rare species I had only heard of or seen in books. Then a new friend, Ed Chapman, invited me on a weekend collecting trip to Bimini in the Bahamas. That was it for me. Hooked on the adrenaline rush, after that I lived for the next experience.

A tragic car-versus-horse accident killed my beloved “Big Red” and left me with a steel pin in my ankle. Further, it destroyed any chance of my serving in the armed forces.

Chalk’s Flying Service Grumman G-73 Mallard landing in Bimini Harbour, 1965.

In the Mexican desert, 1966.

After graduation, I took a labor job with Forest Products, an industrial lumber yard in Port Everglades. I learned what it takes to be a man and how to hold my own in the real world. Not a career of choice, I kept searching and found work with Florida Power and Light Company (FPL) to start in fall. Work would soon limit my time off to weekends and ten days’ vacation, so I headed to Mexico, solo, in September 1966, driving my new Ford Bronco roadster. Ten days gone, and thousands of miles driven across the Gulf Coast and into Mexico, to Veracruz and Mexico City and back. A giant odyssey, in a time when such a trip was still possible and not completely foolish.

Marriage came next. Too early, spurred on by the fateful accident. We made the best of it. My continuing with reptiles became a commercial venture, which helped with finances but strained domestic relations.

Next came Haiti, an expedition of another magnitude. The most impoverished nation in the Western Hemisphere. It was gritty, dirty, and dangerous, but oh so fascinating. Reptiles galore and thrills I could have never imagined.

Men and boys with snakes tied to sticks in Limbe, Haiti, 1967.

People gather round as I examine snakes. Limbe, Haiti. (Photo: Ed Chapman)

A 1967 move to Bradenton, on Florida’s Gulf Coast, changed many things. Work became much more intense, with more important jobs as I advanced. Another Mexico trip included my wife. It was a grand adventure too, but not the same, having to tame things some with a more delicate passenger. Travels to Haiti and the Bahamas continued and became more frequent. Each one a valuable experience, not to mention an addictive adventure.

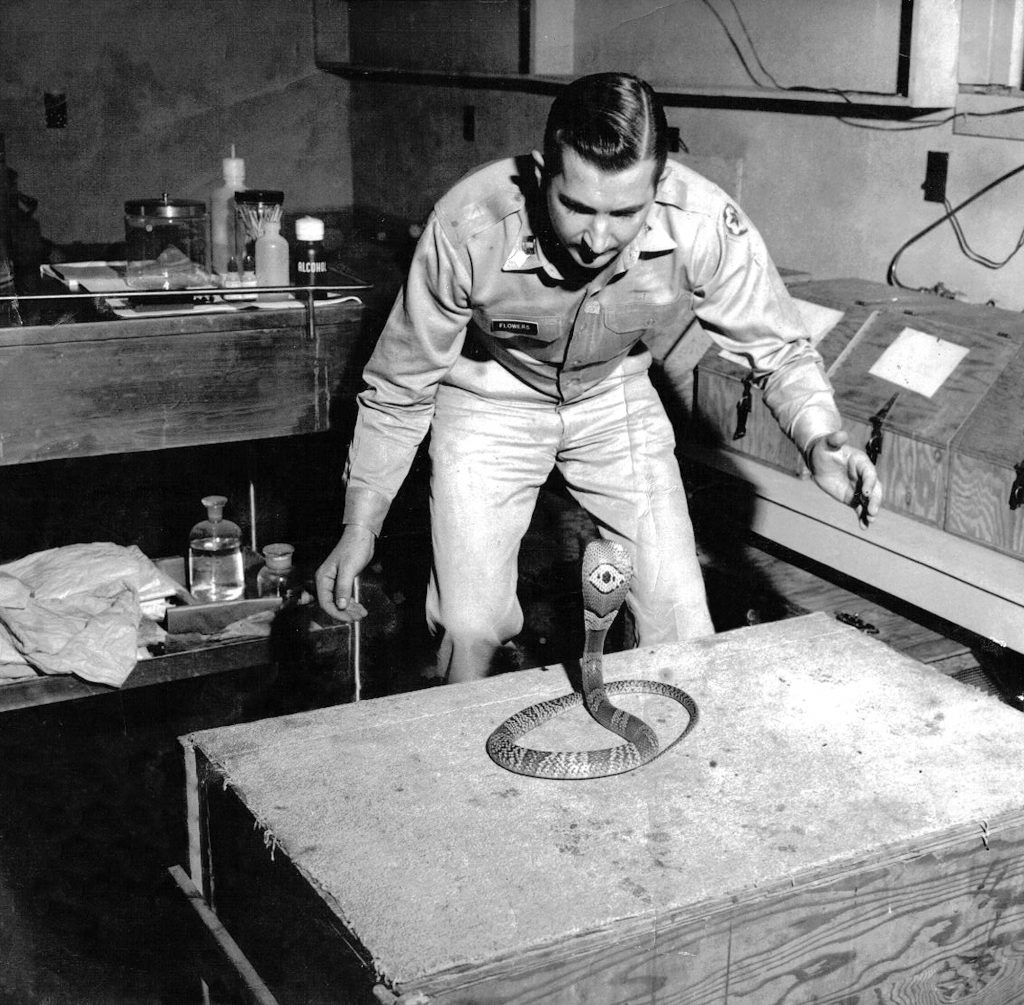

In between, a most memorable and life-changing journey to Costa Rica began in summer of 1968. On the way, I stayed over two days at each stop, in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua. The trip overlapped that of US President Lyndon Johnson, and was interesting, exciting, and harrowing. In Costa Rica, Major Herschel H. Flowers, US Army, met me in his jeep. For the next two months I shared his home where he kept his laboratory and snake colony.

Major Flowers worked since 1965 in Costa Rica to produce a better anti-crotalid polyvalent serum, and an anti-coral serum. Aside from their obvious humanitarian uses, such serums are important should the US become involved in any conflict below our border. My job was to help, and the major trained me in every aspect of the work, from venom extraction, to record keeping, and maintenance.

In 1963, then Captain Flowers, prepares to capture a cobra in his Ft. Knox lab. (Photo: Col. Herschel H. Flowers family archives)

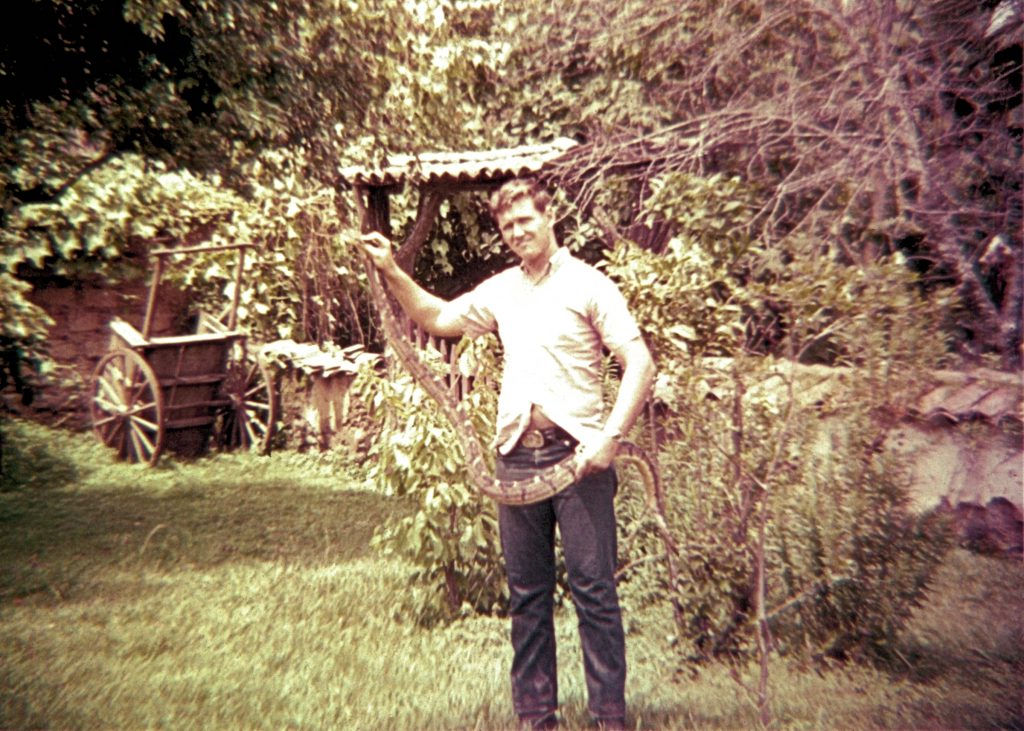

The author holding a large Bushmaster, Costa Rica, July 1968.

During my stay, the best parts for me were the field trips to snake collecting stations, culminated by a major expedition to the Atlantic coastal lowland jungles. Incredible experiences followed, including life and death close calls. In the middle of my Costa Rica stay, we flew to Panama to aid a snakebite victim who passed before we arrived. Overall, the experience cemented my life’s direction, my resolve to continue the path towards a life of exploration.

My connections with other herpers grew. I met and traded with people across Florida, the South, and in countries from Colombia and Pakistan to South Africa. Trips to several Bahamian islands and Haiti continued, using the specimens we collected for trade across the globe. With little warning, a strike at FPL put me out of work for an unknown time span starting in October 1969. Never letting an opportunity pass, Ed Chapman and I head back to Haiti for a less time-restrained trip. Why Haiti again? Aside from the incredible reptiles, it’s the adrenaline-fueled adventures that get in our blood and draw us back, time and again.

Upon return from Haiti, the strike was still in effect, so I headed for the Bahama Islands in my boat, for a solo collecting trip with grandiose plans to visit several islands.

Ed Chapman removing a boa lashed to a stick in Limbe, Haiti.

My boat docked in Bimini for the first leg of a Bahamian journey.

In Bimini, the folly of my scheme became clear, so I left my boat and flew on to Andros Island. Incredible collecting followed, not without hardship, then back to Bimini and home. An extensive collection of snakes from the Caribbean, and local specimens sent to Austria, got in exchange rare European and Mediterranean reptiles. Many outstanding specimens, including lizards, several species of rare vipers and colubrid snakes.

Back to work, our Bimini adventures continued, then in 1970, an Englishman came to visit. Along with Dick Bartlett, we collected in Okeetee, South Carolina, then he and I made a trip to Haiti. It was a true adventure with hair-raising, death-defying close calls, and lots of fabulous specimens.

In 1971, Ed Chapman suggested we investigate Exuma, in the Bahamas, in search of rare rock iguanas. He couldn’t make the first trip, so I’d go alone to scout locations to return later and collect. In the island chain, nestled between inky-blue deep Atlantic waters and the aquamarine colors of the shallow Exuma Bank, it was love at first sight. On my third day, landfall on an uninhabited island was to last for an hour, but the boatman, instead, abandoned me. Without water or food, over the next five days, I almost perished before a fortuitous rescue. Saved by angels.

Surviving the ordeal changed me, at least partly for the better. As happens, the misfortune led to opportunity, and we returned to visit the islands many times over the next couple of years.

Beach on western shore of Gaulin Cay, Exuma, Bahamas, a true desert island.

A crowded Haitian town

Haiti was off limits to us because of turmoil following the death of President “Papa Doc” Duvalier. When things settled, we again made the trip to the mysterious island nation. This time, with two extra men along, making for logistical problems and interesting interactions. This trip too was fraught with danger, near fatal encounters, and plenty of comical incidents.

In 1973, Erich Sochurek visited Florida for collecting excursions around the Everglades before our grand trip to Mexico. His having been a German POW in the US during WWII led to a newspaper interview. In Mexico, we found many species of rattlesnakes in the Veracruz highlands, beaded lizards, and other desirable species along with tarantulas and a load of ancient artifacts in Colima.

Then disaster struck when our permit expired before we reached the border. US Customs impounded our truck. We rode a bus home. Ed Chapman came to our aid, got the truck back into Mexico, but lost the snakes trying to cross the border….

Depressed after the incident, to make things even worse, I suffered a bite from a venomous bamboo viper from Thailand. An eight-day stint in the hospital ensued while doctors struggled to save my fingers.

Trimeresurus popeiorum like one that bit me. (Photo: Thor Hakonsen)

Shack on Man-o-War Bay, Inagua, where I lived with a local hermit.

A few days after returning home, FPL again went on strike. With a still healing right hand, I did what I could to earn a living, before getting an offer I couldn’t refuse. Don Hamper, a collector in Ohio, offered to pay my expenses and a daily stipend, to venture to Inagua in the southernmost Bahamas and then go on to the Caicos Islands. He wanted two species of rare insular boas, and whatever else I could find. What ensued was an adventure of epic proportions. I met famous men, counted flamingos, dodged moray eels, and found drama.

Inagua is vast and wild. Scientists only knew of three specimens of the snake I sought, caught in the 1930s. After many trials, difficulties, and dangers, I met with success, finding two. Next was getting to the Caicos, by hitching a ride on a plane bound for Haiti. Once there, I met up with old friends and introduced a new traveler who I met after his shipwreck on Inagua.

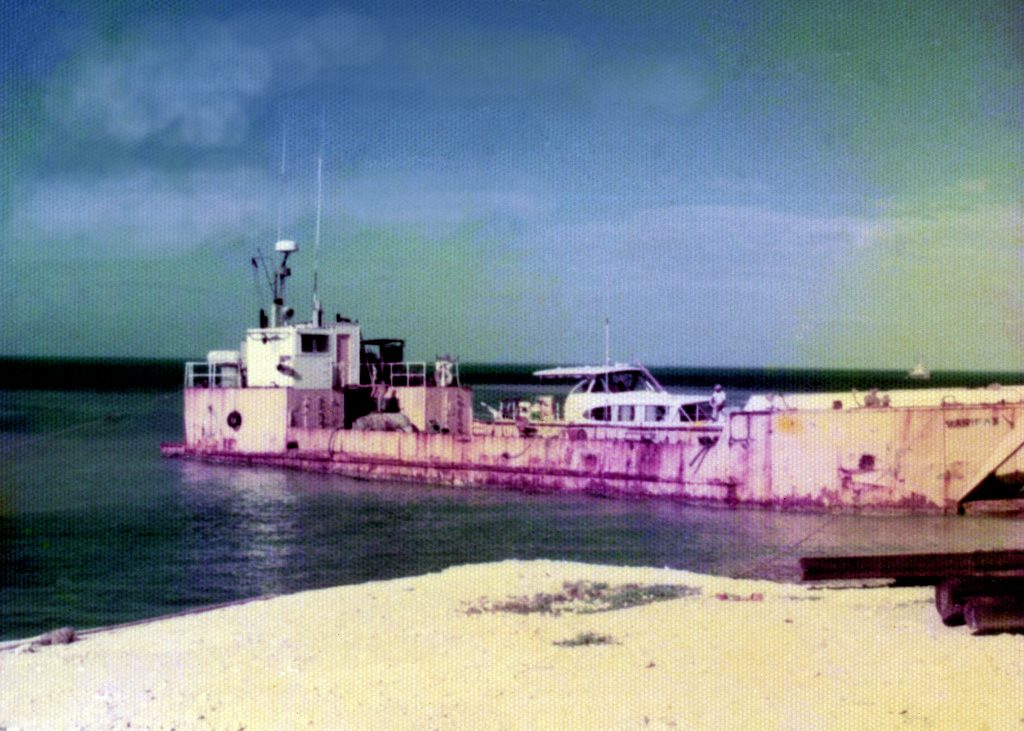

Voodoo, intrigue, and deadly violence marred the trip, but the flight to Caicos brought a serendipitous meeting with a man who helped me in a major way. On South Caicos, he offered an old, derelict, LCT barge as home base. Excursions to North Caicos, East Caicos and a solo ten-day stay on uninhabited Little Ambergris Cay followed. Many specimens made the expedition a success and unforgettable experiences made it a journey of a lifetime. I was away from home, out of touch, for three months.

LCT barge on South Caicos, my home base for exploring the islands.

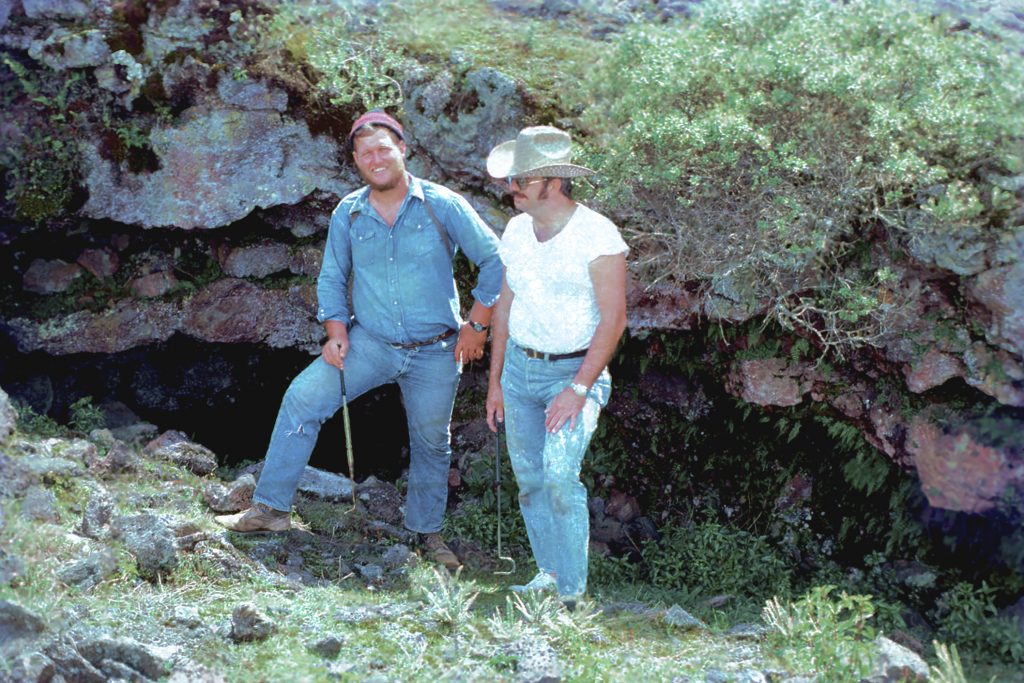

Author (L) with Dick Bartlett in Las Vigas, Veracruz, Mexico, 1974. Photo: Gerald Keown

Upon return in early 1974, a perceived betrayal of confidence by a friend leaves me demoralized. Dick Bartlett suggests a Mexico trip, to refocus my energy. We meet sheriff’s deputy, and snake hunter, Gerald Keown in Texas and take his pickup camper on a wild and raucous jaunt across the wilds of the Mexican Plateau and on to the jungles of Colima. It’s a glorious excursion, filled with laughter, camaraderie, and outstanding specimens. A tonic that I needed.

The following year, Dick and I with our wives head off to the high jungles of Venezuela. It’s my first time on the South American continent. The journey is outstanding, visiting the cloud forests of Rancho Grande, then the llanos, where we meet caiman, tegus, and electric eels. When the day of departure comes, I am persuaded to stay on another week, to take full advantage of our plant collecting permit. Trips to nearby national parks are interesting, but not worth the extra stay. Then comes a trip to the wet jungles of Guatopo and an expedition to remember. Wildlife, rare plants, and the splendor of unspoiled nature. It’s a memorable trip for several reasons. Not least, after returning, they discovered two of the plants I collected to be new to science. The Smithsonian’s Dr. Robert Read and Clyde Reed, of the Reed Herbarium, named them in my honor.

The castle at Rancho Grande, Henri Pittier National Park, Aragua, Venezuela, 1975.

Crossing the Aponwao in the Lost World. Center L, Henrique Graf, center R, Lew Ober. Right foreground, Tina Graf, 1976.

A new acquaintance in Henrique Graf of Caracas becomes a lasting friendship when he visits our home in Florida. A return trip to Venezuela, at his invitation, begins in 1976. Professor Lew Ober, from Miami Dade College, comes with us. His specialty is reptiles and working with him is the last field experience I’ll have in herpetology. We explore the famed Lost World among the table-topped tepuis and wild Pemon tribes for six weeks. After uncounted adventures, we return with many rare bromeliads and orchids and a lifetime of memories.

I begin a life dedicated to collecting and growing bromeliads and other rare exotic plants. First, divesting my remaining reptile specimens and equipment. In the same year, I establish Tropiflora, a plant nursery, which becomes my life’s work. Today it is still going strong, shipping plants worldwide.

Life takes many turns. My wife and I separate after 17 years of marriage, and I continue with the travels and nursery. Linda and I marry in 1984. She becomes my partner in every way, traveling the world beside me on countless collecting expeditions and speaking engagements. Robin and Scott, our two young children, go with us on her first trip to Venezuela. We soon realize they might be too young for jungle travel. It’s fun, but a handful.

Tropiflora greenhouse in 1976.

Linda sharing treats with Indian children, Ecuador, 1986.

Linda next comes on a real expedition to Ecuador. It’s my second, after first taking my friend, Wally Berg. Linda excels, doesn’t complain during hardships but suffers when she encounters poverty. She hands out treats: candy and supplies we no longer need, and the response is heartwarming. This became a regular part of our future trips.

Tropiflora aerial shot, 2012.

As the nursery grows, so does our need for plants. A move to a Sarasota property allows room for expansion. We add new greenhouses until we have over six acres under cover. To sell our plants, we take them to shows and exhibits and expand our mail order business. Speaking engagements built around our many travels take us across Florida, the US, and to many countries. Over the years, we speak in Venezuela, Brazil, Bahamas, Australia, New Zealand, Philippines, Java, Singapore, and Thailand. While in these locations, we take time to explore and collect, when possible, and to meet potential customers and suppliers.

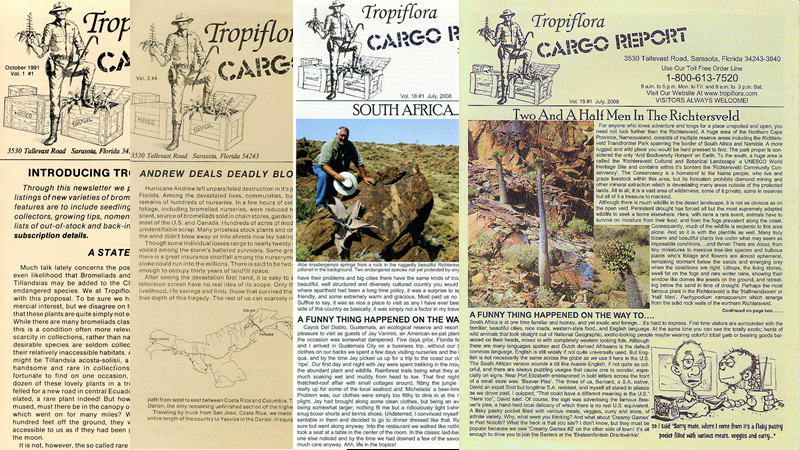

In 1990, we began the Cargo Report, a newsletter/catalog featuring not only plants with illustrations and descriptions, but stories from our travels. Lots of adventures and fun. The Cargo Report is a success and becomes more frequent, growing from a few pages to 16 and from black and white to full color. But the world keeps changing and with the internet comes new ways to sell. Printing and mailing become too slow and costly to be worthwhile. A new weekly offering of rare plants we call the VIPP, sent by email, becomes the Cargo Report’s replacement. For that, we need stories each week! A giant task for me, but good, I suppose, for writing experience.

Sample Cargo Report covers.

Exhibit at the 2006 Singapore Garden Festival, just prior to opening.

In 2005, we’re bowled over by an unbelievable proposal. A good friend, famous and well connected in Singapore, came to us with what was then little more than a pipedream. His idea was to create the world’s most modern and incredible garden in Singapore. On a Singapore visit I made earlier, he had shown me land he proposed to get for the garden, but his talk of the project seemed far-fetched. Now he’s here, proposing that they buy our entire plant inventory as an anchor collection for the garden. Okay, still pie-in-the-sky, but his determination stuns us. What came next was a massive display at the first Singapore Flower and Garden Festival in 2006. Under direction of famed Osaka landscape designer, Junichi Inada, it took weeks to build. We stayed six weeks, over Christmas and New Year. The display was beyond exceptional and won the silver medallion.

Our travels continue, trips to Central and South America and SE Asia several times each year. Hundreds of collecting trips, shows, festivals, and lectures. Life is a whirlwind. A few years ago, I pulled back from the nursery. Robin and Scott, now middle-aged, are running the nursery day to day, along with our faithful crew, many of whom have been with us for well over 20 years. Now I write. Linda still goes to work to supervise and visit. She loves meeting the people from across the world who come to our nursery every day. If time permits, she gives them personal treatment and a tour. No one leaves, not feeling welcome.

Dennis and Linda at the Edge of the Word marker, Tasmania, Australia, 2015.

So, there you have it, a thumbnail version of my life, and ours, Linda, and me together. As you can see, I have received many blessings. Hopes are that writing will allow me to share the countless adventures we have enjoyed in books, to bring you along to see the amazing wilderness, incredible plants, wild animals, and taste the experiences that have made our lives unique and unforgettable.